TextualExhibition Text

HdM Gallery | Marcella Barceló’s Idea of Nature: Calling Her Own “Ludmila’s Planet”

Introduction:

When approaching Marcella Barceló’s painting as a case study of ecofeminist practice, curator Evonne Jiawei Yuan intuitively alchemizes her recent readings and musings on science fiction, philosophical prose, and critical theory into an entry point for us to access the recurring motifs in her recent works.

Text:

① Twinship

“Had Ludmila possessed some magical power that had allowed her to see into the distant past, if not the future? Was that even a viable theory in this day and age? Could everything instead just be an enormous coincidence? But then, what were the chances that an imaginary planet, flawlessly conceived though it had been by a massively gifted artist, was virtually identical to one later discovered in real life far off across the universe?” 1

– Excerpt from Choyeop Kim’s supernatural sci-fi novelette “Symbiosis Theory”

In the short story “Symbiosis Theory” (2019) written by Korean author Choyeop Kim, Ludmila, the protagonist who has been recognised as an artist dedicates her life to painting “that place lit in an anodyne blue glow.” It is an unknown planet pieced together by her fragments of memories and she later dubs it by her name. When people feel immersed in the beautiful scenery of “Ludmila’s Planet,” they realise that, just like the feminine lead, their spiritual awakening to innate wisdom also comes from “them” parasitically embedded in the brain that were originally born on the “Planet” – those alien infants cross-referencing the present “us”.

It is not surprising that such kind of characterisation based upon the studies of symbiogenesis 2 and self-psychology 3 arising in the 1970s and 1980s – literally infusing elements of biotech and psychoanalytic thoughts – is not only a common topic in sci-fi writing, but more and more often being appropriated into a certain form of archetypal figure by artists who are exploring new realities of the post-Anthropocene.

In this vein, Marcella Barceló’s ecofeminist painting fully exemplifies the foregoing conception, and her personal story also echoes Ludmila’s character arc. Raised in an artistic family, she was encouraged to inventively engage with a variety of materials from an early age. Meanwhile, she spent her childhood amidst the natural splendour of Majorca, an island in the western Mediterranean, where endangered marine and terrestrial species, coral reefs, subterranean lakes, karst caves, as well as other forms of water-sculpted landscapes, all deserved her close observation. The underlying relationship between the two culminates in the autobiographical characteristics of her works.4

Just as Ludmila stubbornly refuses to let go of the blurry imageries brought by one of “them”, Marcella centres her artistic practice around the “alter ego” that longs for the verdant cradle of her homeland. The allegorical choice conveys her deep connection to the natural world and her yearning to return. It casts a direct reflection of her defensive affection or impulse and is projected into the twinship experience that she repeatedly emphasises.

In Stars at Tallapoosa, Muy’ingwa, Pollinose and Ikiriyō, Marcella portrays sisters in solidarity, either side by side or back to back, as they draw on each other’s strengths to foster growth, a testament to their resilient bond. Though united, each figure retains her unique individuality. Notably, the artist renders the female bodies nearly translucent, under no restraint and relaxed, evoking her unfettered childhood and naivete, away from the grasp of urbanity coined with its industrial surroundings, and the constructs of reality.

② Xanthos & Bluets

In “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” Marcella’s debut presentation in Mainland China, two acrylic paintings out of over twenty works on canvas, wooden panel and paper, are drenched in a sea of golden-yellow tones, namely literalising the interpretation of the title – “what is gold does not last long”.

Yellow was not a precise expression in the colour perception of the ancient Greeks. Instead, they used the word “xanthos” to describe a wide variety of yellows and their essence – the glittering fair hair of the gods, the warmth of lynx stone, the reddish flames of fire, etc., with movements and flickering shimmers. Plato even associated the golden-yellow with morality and sanctity, as an epitome of the ideal spirit and even transcendence that links man to the ethereal, and to eternity itself.5

In Heat Waves, Marcella applies various shades of yellow to communicate a touch of fever under the sun’s radiation, highlighting the lingering light of the evening glow that dissolves into the clear sea, all at the same time contouring the emphatic silhouette of her own body in pale skin submerged in the water. Or rather, it is the cultural factor and meta-narrative carried by the particular colour that gives the artist the most control over such compositions, which is also the best illustration of her desire to integrate with the situated worlds in a non-human manner.

“In many of her early pieces, Ludmila’s Planet is rendered in a more or less abstract style. Themes of swirling blue and purple present it as a home to multitudes of creatures, some with stable forms, and others with fluidly shifting ones. Much of the planet’s surface is covered by an ocean teeming with drifting bioluminescent amoebas, to which the planet owes its peculiar blue glow.” 6

– Excerpt from Choyeop Kim’s supernatural sci-fi novelette “Symbiosis Theory”

However, the primary colour that is more dominant in terms of volume among all the exhibited works this time is actually blue. In Illa, which also has a golden yellow foundation, Marcella invests a small amount of blue to accent the fish swimming with her and the ridges of the continuous mountain peaks in the background. This contrasting palette of light and dark, warm and cold, is commonly seen in classical European portraiture, and the artist mediately invokes a degree of “humanity” in nature.

Perhaps more crucially, the saturated blue in richer textures serves to balance the greenish and purplish tones that frequently appear in the artist’s palette. Her keen grasp of this hue may be related to her perceptual experience of observing the underwater wild through long periods of diving, but it is also related to the formal study of the modern colour system that she has acquired through her academic training. The preference for a vibrant phthalocyanine blue, a shade pioneered in the 1930s that invigorated modernist art, is particularly telling of her stylistic influences.

It is true to say that Marcella has “(re-)claimed” the nature which nurtures her artistic journey, especially through the layered blending of blue. Blue marks the transition from dusk to night and adds a sense of solemnity when tinged with a hint of purple. If one certain colour can be declared as an artist’s statement, then in Marcella’s ecofeminist approach of painting, blue marks a domain of serenity, a vision of paradise, and a nod to “Ludmila’s Planet” which is also dominated by this colour.

Maggie Nelson, an American poet, has also made a similar description. The special thing about blue is that it is solitary yet exalted, projecting a field oscillating between nostalgia for a distant memory and compassion for a futurity. Through a constant look back to personal history, Marcella contemplates her intertwined existence with nature, suggesting that to have nature preserved, at its core, to care for oneself.

“The half-circle of blinding turquoise ocean is this love’s primal scene. That this blue exists makes my life a remarkable one, just to have seen it. To have seen such beautiful things. To find oneself placed in their midst. Choiceless. I returned there yesterday and stood again upon the mountain.” 7

– Excerpt from Maggie Nelson’s lyrical essay of prose-poems Bluets

③ The Carnivorous Plant

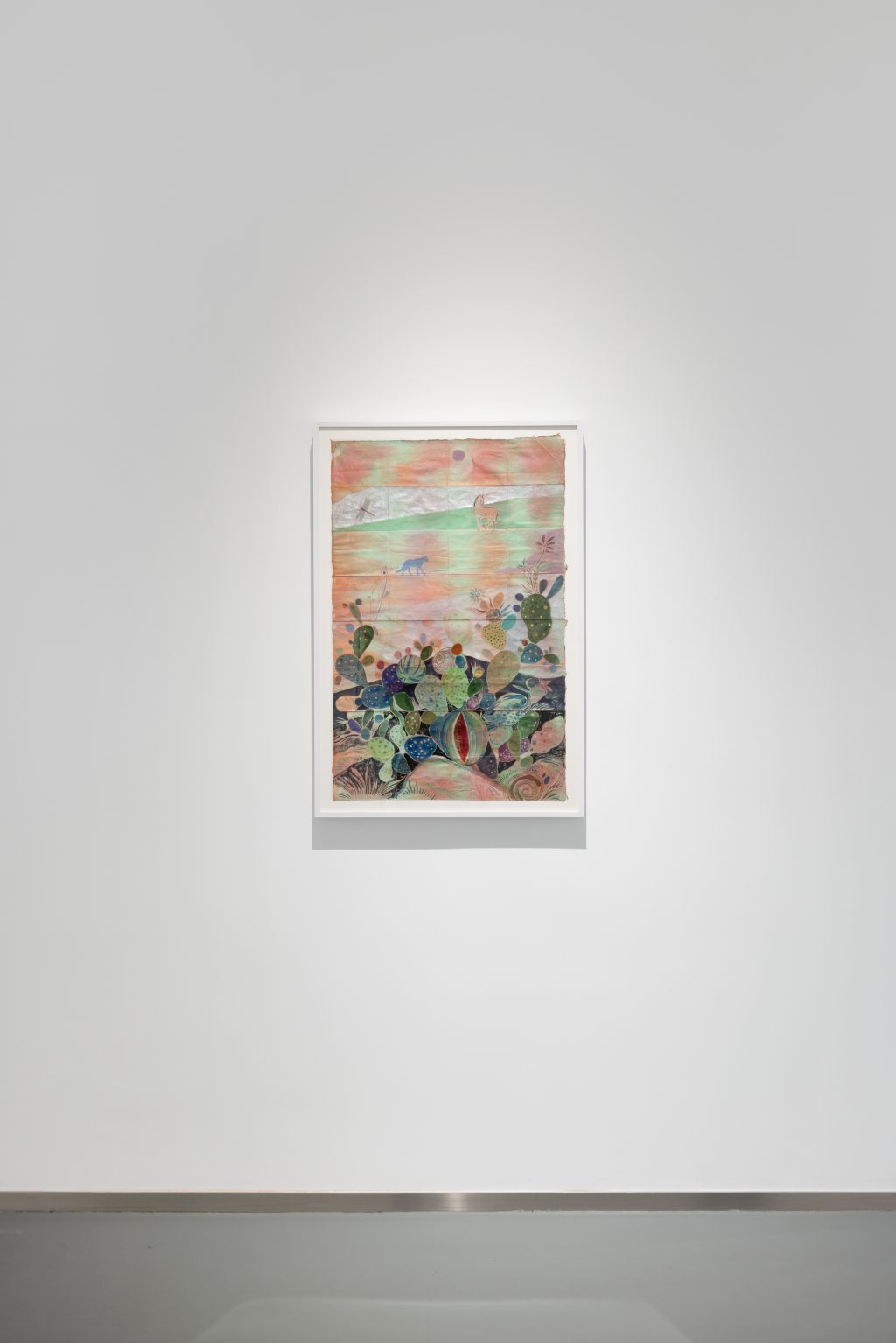

Marcella often features elements such as the Venus flytrap and cactus, plants well-acclimated to Majorca’s landscape. Notably, the Botanicactus – a vast cactus garden spanning 150,000 square meters – is nestled in Ses Salines on the island’s southern coast. These plants are characterised by their spiny leaves, a natural adaptation for both self-defense and predation. The Venus flytrap, maintaining dual roles as both producer and consumer in its ecosystem, is emblematic in her work, perhaps a subtle allusion to the complex human psyche, mirroring the interconnectedness seen in the imagery of twinship.

Marcela’s fascination with the symbolic meanings of such species may be related to the way she defines her own “interiority” in the physical environment. In Dionaea Uniflora, she becomes incarnate as the rhizome of the carnivorous plant, which is also the premise of her focus on nature: predatory behaviour and social reproduction, the earth’s ecology and political power. She portrays the current world’s systems as unhuman, “a cannibal that devours its own vital organs,” 8 with its finite capacity for recovery, cannot always redress.

Marcella’s ecofeminist painting with its surreal qualities alludes to the existential crises of our times: climate change, rising temperatures, melting ice caps, rising sea levels, biodiversity loss, mutations, droughts, floods, barren zones, etc. Taking Actiniaria as an example, perennial hydroid coral, desert cactus, and human skull all at once constitute an eschatological sign. This work may be the one that most closely captures an apocalyptic vision, yet the artist deliberately places herself as part of the scene, affirming the “hypothetical symbiosis” that is as compelling as it is complex.

Notes:

1. Choyeop Kim, “Symbiosis Theory,” trans. Joungmin Lee Comfort, Clarkesworld Magazine, Issue 159, December 2019, https://clarkesworldmagazine.com/choyeop_12_19/

2. Symbiosis, which simply means members of different species living in physical contact with each other, is crucial to the origins of evolutionary novelty. For more details, see Lynn Margulis, Symbiotic Plant: A New Look At Evolution (New York: Basic Books, 1999).

3. Twinship (alter ego) means to feel a sense of likeness with others. It is of the three specific types of transferences that reflect unmet self-object needs. For more details, see Heinz Kohut, The Analysis of the Self: A Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders (New York: International Universities Press, 1971).

4. Martin Mayorga, “It’s a grotesque wonderland world! (Interview with Marcella Barceló)” (14 May 2020), Dateagle Art, https://dateagle.art/marcella-barcelo-interview/

5. Maria Michela Sassi, “Philosophical Theories of Colour in Ancient Greek Thought and Their Relevance Today,” Ancient Philosophy Today: DIALOGOI 4.2 (2022), 155–175; Maria Michela Sassi, The Science of Man in Ancient Greece, trans. Paul Tucker (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2001).

6. Kim, “Symbiosis Theory,” https://clarkesworldmagazine.com/choyeop_12_19/

7. Maggie Nelson, Bluets (Seattle and New York: Wave Books, 2009), 3.

8. Nancy Fraser, Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet—and What We Can Do about It (London and New York: Verso, 2022), 84.

Date: 2024.3.30